Yossi Alpher is an independent security analyst. He is the former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University, a former senior official with the Mossad, and a former IDF intelligence officer. Views and positions expressed here are those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent APN's views and policy positions.

Q. A third Knesset election within a year is now a certainty. We have nearly 80 days until March 2 to discuss it. Perhaps we can, for a while, postpone detailed analysis of party mergers and of Netanyahu’s campaign tricks and catch up on regional and international issues that you have had to neglect recently.

A. Good idea. But let’s not forget to come back in the weeks ahead to the sorry state of Israel’s health, education and transportation infrastructures after ten years of Netanyahu and one year without a proper budget. And the December 26 Likud primary between Netanyahu and challenger Gideon Saar is looking more interesting by the day.

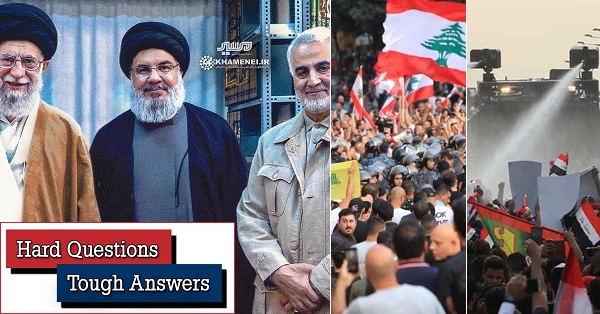

Q. In precisely the spirit of catching up on relevant regional developments, what is the strategic significance of the current and recent mass demonstrations against the governments in Lebanon, Iraq and Iran? What do they mean for Israel and for the US?

A. In all three countries, the protests focus on corruption, poor governance and

economic crisis. In all three, masses of protesters appear to be essentially leaderless and acting spontaneously

(though the US and Israel are regularly blamed as instigators by the powers-that-be).

We are witness to a regional phenomenon of upended national social contracts. It appears to be an outgrowth of the

Arab revolutions of recent years and has, in the past year, included removal of leaders in Sudan and Algeria by the

military under pressure from angry publics fed up with massive corruption. At the broadest level, Israel must be

concerned lest similar anarchic protests erupt really close to home--in the West Bank and Jordan, for

example.

Yet each country’s case is different. In Iran the protests are over, having changed nothing at the institutional

level. As in past instances, the Islamic State has proven it possesses the tools of force and oppression--and the

resolve to use them--to quell protests by the economically deprived and by ethnic minorities. The protests were

particularly violent this time, as was the government response. But it’s over. Those in Washington and Jerusalem

who dream of regime change in Tehran should once again recalibrate their expectations: the Islamic Republic knows

how to survive.

Lebanon, Israel’s neighbor to the north, offers a startling contrast to Iran because it is so ethnically diverse

and because protests there against widespread corruption have brought down the government and paralyzed the

country. The economic situation is catastrophic: the national debt is now out of control, credit is frozen and the

citizenry cannot withdraw its money from the banks. Recall that Lebanon’s banks once rendered the country the

Switzerland of the Arab world.

What for months were remarkably peaceful mass demonstrations in Lebanon’s cities are now turning violent. It

doesn’t help that neighboring Syria, torn by years of civil war, is also broke and chaotic.

From Israel’s standpoint, the Lebanese actor to watch is Shiite Islamist Hezbollah with its close Iran connection.

In recent days, Hezbollah has begun playing a role in violently suppressing demonstrations. Any development in

anarchic Lebanon that empowers Hezbollah is bad news for Israel and, less directly, for the US.

In Iraq, which like Lebanon is highly fragmented ethnically and politically, protesters have also forced a prime

minister to resign. Here too, no compelling new leaders or opposition ideologies have emerged. Here, unlike

Lebanon, violence and bloodshed have from the outset characterized not only mass protests but the response of

Shiite militias affiliated both with the Shiite-dominated establishment and with neighboring Iran.

Indeed, Tehran’s concern regarding the stability of its Iraqi client-state and the hostility displayed against Iran

even by Iraqi Shiite demonstrators (e.g., burning Iranian consulates in the Shiite south of Iraq) appears likely to

drive Iran to increased intervention. At the regional level, possible setbacks in Iraq and Lebanon threaten Iran’s

grand strategy of spreading its hegemony westward. As for the US, there is no longer much left of the governing

apparatus installed by Washington after its 2003 occupation of Iraq.

Both Israel and the US should be concerned lest the outcome of the current unrest in Iraq is even more Iranian

influence and quasi-military presence. Yet there is not much either can do about it. Or should do: history shows

that meddling by either Israel or the US in the affairs of Arab states (and Iran) generally proves

counter-productive. Recall the US in Iran in 1953, in Lebanon in 1958 and in Iraq in 2003, and Israel in Lebanon in

1982.

Q. Apropos meddling, lately we hear more and more talk about “deep states”. Does Israel have a “deep state”? Does the US?

A. The term deep state has been ridiculously distorted of late by President Trump and

others from the American and Israeli right wings who seek revenge against legitimate government gatekeepers who

criticize, impeach and indict them. First, let’s clarify what deep state should mean.

“Deep state” began as a Turkish term (derin devlet) and derived from the activities of secret societies late in the

Ottoman Empire. It described the security and intelligence apparatus in a state (Turkey) that is ostensibly

democratic and transparent, with a government and judicial system, but in reality is ruled behind the scenes by

that very apparatus. In Turkey of the 1970s the generals ruled behind the scenes; the elected president and prime

minister had no real power unless the generals gave it to them.

It was only after Recip Tayyip Erdogan came to power in 2002 that Turkey’s security establishment was brought under

the genuine control of the elected government and ceased to function as a deep state. Erdogan has mercilessly

hunted down real and imaginary military and other opponents in the course of concentrating strategic

decision-making power in his own hands, becoming alarmingly autocratic. In so doing, he has oppressed the

institutions of a democratic state like a free press and tried to impose strict Islamic values and institutions. So

Turkey may today be a less than democratic state. But it no longer has a “deep state” apparatus. When it did, it

was also not democratic. Today, at least what you see is what you get.

“Deep state” has also in recent decades and recent years been invoked to characterize the behind-the-scenes

influence of the security establishment in Arab states undergoing revolution. For instance, in Egypt after the

removal from power of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 and prior to the overthrow of a democratically-elected Muslim

Brotherhood government by current President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi in 2013, the military intelligence apparatus led by

al-Sisi could be characterized as a deep state.

In Israel and the United States, as in other functioning democracies where elected civilian leaders can appoint and

remove the heads of the security establishment at will, there is no deep state. This does not mean that the Israeli

and American security establishments are devoid of influence over decision-making processes. In Israel in 2012, the

IDF and the Mossad effectively nixed PM Netanyahu’s plan to attack Iran’s nuclear infrastructure. In the US, we see

the military repeatedly and “creatively” interpreting President Trump’s demands to remove US forces from Syria so

as to leave some there.

But in both these cases, as in numerous others, the elected leader is fully cognizant of what his security chiefs

are saying and doing (whether Trump understands is another issue) or for that matter what his judicial

establishment is saying. The leader can if he wishes--subject to constitutionally-embedded legal constraints that

themselves run counter to a deep state--fire his security chiefs and take open issue with judicial decisions.

Trump and Fox News can call the FBI or the American media “deep state” if they wish. And Netanyahu can accuse his

legal advisers (whom he himself appointed) of fomenting a coup. But these institutions are neither deep nor a state

nor acting behind the back of the prime minister.

Q. Can you explain how the original deep state worked in Turkey?

A. Here is an example from the Israeli experience. In 1958 the intelligence

establishments of Israel, Iran and Turkey established Trident, a secret tripartite security alliance directed

against an aggressive Arab world and against Soviet incursion into the Middle East. Israel’s Mossad, in

coordination with the IDF, played its role in Trident with the full knowledge and approval of a series of prime

ministers and special Knesset intelligence watchdog committees. Iran’s Savak (secret intelligence agency) and army

acted with the full knowledge and endorsement of the sovereign, the Shah, albeit within a brutally autocratic

setup. The Iranian state was highly oppressive, but not “deep”.

In Turkey, however, the security and intelligence establishments acted autonomously. In 1959 IDF Chief of Staff

Haim Laskov and his Turkish counterpart could lay plans for a joint invasion of Syria--Turkey from the north,

Israel from the south—without PM Adnan Menderes or his government being brought into the picture (that invasion

never happened).

In 2010, after the Mavi Marmara incident (in which Israeli commandos intercepted a Turkish ship bringing Islamist

activists to Gaza, inadvertently killing 9 Turks), I sat down with the Turkish charge d’affaires in Tel Aviv to

discuss our radically contrary understandings of what had happened to our two countries’ once flourishing

relations. In an effort to add some depth to the conversation, I noted our past history of close strategic

cooperation under Trident.

“What was Trident?” she asked. She had no idea. A Turkish-Israeli strategic relationship or history had never been

mentioned to her in 15 years in the Turkish Foreign Ministry. She couldn’t understand why Israelis referred to the

two countries’ then twice-yearly diplomatic conferences as “strategic”. Turkey’s deep state had kept its own

Foreign Ministry completely in the dark.

Q. Finally, how does the outcome of the UK parliamentary elections affect Israel?

A. The outcome deals a blow to Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-Semitism. That is good news for all

Jews. Boris Johnson’s triumph strengthens the Trump-Netanyahu political and economic world view. That is seemingly

good news for those in Israel who believe that ignoring the Palestinians in our midst and rejoicing over Trump’s

rhetoric regarding Jerusalem, the settlements and the Jordan Valley actually serve Israel’s long-term

interests.

Finally, the European ideal has been weakened by the British public’s affirmation of Brexit. In the long term, and

seen against the backdrop of two world wars in the previous century, that is bad news for us all.

For previous editions of Hard Questions, Tough Answers, go to the Index Page.