This week, Alpher discusses the new Middle East reality Israel confronts as a consequence of the US-Russian deal regarding Syria's chemical weapons, what lessons and conclusions can be taken from the massive commemoration in Israel of the 40 years since the outbreak of the 1973 war with Egypt and Syria, the significance of a ruling by an Israeli judge two weeks ago concerning Palestinian incitement against Israel, and the contribution of Osama al-Baz, who died Saturday in Egypt, to peace.

Q. What new Middle East reality does Israel confront as a consequence of the US-Russian deal regarding

Syria's chemical weapons?

A. On the face of it, Israel is about to see a traditional enemy on its northern border lose its dangerous chemical

weapons arsenal, and this is good news. But the Lavrov-Kerry agreement also raises a host of issues and questions

that at this juncture can only be noted with concern by Israel as topics to be monitored closely in the months and

possibly years ahead.

First and foremost is the question of the roles to be played by Washington and Moscow in the Middle East. Was the

drama we witnessed in recent weeks yet another stage in America's withdrawal from an active security role in the

region, or was it an instance of the successful leveraging of military strength to gain a strategic achievement and

allow others--Moscow--to share the dirty work? Turning to Russia, is it now once again the superpower patron of

Syria--the new "address" for Israeli and US complaints and concerns?

Certainly the maneuvering leading up to this agreement treated observers to radically contradictory concepts of

America's role in the Middle East. Was this one more step in Washington's "war weary" withdrawal, following

Afghanistan and Iraq, as many Israelis and Arabs saw it? Or were American preparations to launch a "limited" attack

on Syria really a cover for yet another Arab regime-change operation following Iraq and Libya--as the Russians and

possibly Syria understood?

Second, will this agreement, which is impressive and comprehensive in its scope, actually work or will it unravel

in the mayhem of Syria's civil war? Can Russia indeed now command Bashar Assad to do its bidding, to the extent of

conceding his strategic weaponry, or are we witnessing clever Syrian and Russian smokescreens? If the latter, will

the US eventually make good on its threat to attack Syria, or is the message of recent presidential hesitations and

congressional and public opposition that this will never happen on President Obama's watch?

This brings us to Iran. The stage seems to be set for a new and more promising round of negotiations over Iran's

nuclear program, with a seemingly moderate and reasonable Iranian president meeting an American-Russian coalition

intent on solving yet another Middle East non-conventional proliferation issue through peaceful means. Obama even

insists that the option of American military action against Iran is still on the table. Does Iran see it that way?

Does Russia?

The Israeli political leadership has issued declarations in recent days to the effect that Israel understands it

must be ready to go it alone militarily against Iran if diplomatic efforts fail. This seemingly reflects a loss of

confidence in the Obama administration's commitment to its "red lines"--one that can only conceivably be dispelled

by means of a rapid and successful outcome in disarming Syria of its chemical weapons.

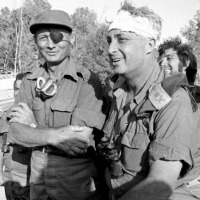

Q. Saturday, Yom Kippur, marked 40 years to the outbreak of the 1973 war with Egypt and Syria. What lessons

and conclusions do you take away from the massive commemoration of this event in Israel?

A. Israelis are swamped by annual commemorations of our many wars and far fewer peace agreements; it's hard to

avoid them and easy to become cynical about them. What made this particular anniversary different and more powerful

in its effect on the public was the release by the state archives of transcripts of remarks and conversations among

the political and military leadership of 1973 in the early days of the war that attest to the near-total

disillusion and despair that overwhelmed them.

One key lesson of the 1973 Yom Kippur surprise that apparently can never be repeated too often is to remain alert

and at all costs avoid an attitude of hubris and condescension toward our enemies--both the identifiable and the

potential--and toward our neighbors in general. This is easier said than done. Certainly, the attitude of key

pro-settler elements in the Netanyahu government toward the Palestinian population of the West Bank and East

Jerusalem--sometimes extended to Jordan as well--appears to be one of pure hubris and condescension. Even the

admonitions of our best friends in the West and here and there (Amman, Cairo) the Arab world are simply brushed

off.

History generally does not neatly repeat itself. What happened in 1973 probably won't happen again. The next

surprise that visits a smug Israeli leadership will undoubtedly be different. This observation is all the more

timely in view of the additional revelations that have been presented to the public on the occasion of this

anniversary.

During the two years leading up to October 1973, Egypt's President Sadat sent provisional peace feelers to Israel

through American good offices. Sadat's messages may have been flawed, and certainly suffered from Cairo's refusal

to deal directly with Israel. But PM Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, intent on winning an election and

happy to argue "better Sharm al-Sheikh than peace", rejected them without even informing the Israeli Cabinet or the

security establishment. Henry Kissinger, first as US National Security Adviser and later as Secretary of State as

well, appears to have connived to let the Yom Kippur War "bleed" Israel in its initial phase because he saw a

painful war as perhaps the only possible catalyst for Israeli-Egyptian peace.

Unraveling this complex of plots, ignorance and legitimate doubts is messy, to say the least. But there is one

obvious lesson: we should be looking harder for peace, even when it appears unlikely.

Q. What is the significance of a ruling by an Israeli judge two weeks ago concerning Palestinian incitement

against Israel?

A. In a Tel Aviv district court, Judge Dalia Gannot rejected legal claims against Palestinian officials for

inciting other Palestinians to commit the terrorist murder of an Israeli some ten years ago. The case, brought by

the victim's family, was based primarily on the research carried out by Itamar Marcus, founder of Mabat, a watchdog

group that monitors the Palestinian media. Gannot, after immersing herself in Marcus' research, ruled that the

instances of incitement he cited were relatively minor and highly selective and relied primarily on marginal

Palestinian publications that do not faithfully represent the Palestinian Authority or the Palestinian

mainstream.

This is an important ruling. Marcus and others on the political right have been trying for years--not without

success--to convince Israelis that the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank incites against Israel and that

Israeli-Palestinian peace cannot be based on a firm foundation until and unless the incitement stops. The fact that

they cherry-pick incendiary statements and articles has largely gone unnoticed by Israeli leaders from Netanyahu on

down, who complain frequently about Palestinian incitement. Nor have most of these "watchdogs" ever paid much

attention to incitement against Palestinians on the part of Israelis, ranging from Avigdor Lieberman and Shas

leader Ovadia Yosef to the curricula of religious and Haredi educational institutions.

Gannot's ruling does not ignore the existence of incitement on the part of Palestinians. But it does call Marcus an

"incompetent" witness and label his extensive "research" efforts inadequate for proving that Palestinian incitement

against Israel and Israelis plays the central role that the Israeli right insists upon. One can only hope that the

ruling will contribute to a saner and more balanced approach to the issue of incitement on both sides.

Q. Osama al-Baz died Saturday in Egypt. What was his contribution to peace?

A. I met al-Baz many times over the years, at conferences in Europe, in Israel, and in his office at the Foreign

Ministry in the heart of Cairo. We once stripped off our shirts in Aspen, Colorado, to compare bypass operation

scars. As a close adviser to presidents Sadat and Mubarak, he was a consistent advocate for peace, both at the

bilateral Egyptian-Israeli level and with regard to the Palestinian issue. He was unorthodox in style and always

ready to think "outside the box". Yossi Beilin related on Sunday that when he was minister of justice under PM Ehud

Barak, he and al-Baz used to fly to London, each from his own country, for Saturday brainstorming meetings at a

Heathrow hotel, then fly home the same day.

Mubarak dispensed with al-Baz's services a few years ago. According to the press, it was because al-Baz had sounded

an alarm about the rising popularity in Egypt of the Muslim Brotherhood. Al-Baz's health was also fading. The

"Israel file" was given to General Omar Suleiman, who died at the height of the revolution. By the time the

Egyptian revolution broke out in Cairo's Tahrir square in January 2011, al-Baz was ready to join the demonstrators.

According to the Egyptian press, he used the occasion to speak enthusiastically and very candidly about the peace

with Israel, advocated working closely with Jerusalem on the Palestinian and other issues, and pointed to Hamas as

the joint enemy of both Egypt and Israel.

He will be missed.