This is the eleventh in a series of reviews of books on Middle Eastern affairs. We asked Dr. Gail Weigl, an APN

volunteer and a professor of art history, to review David Harris-Gershon's new book.

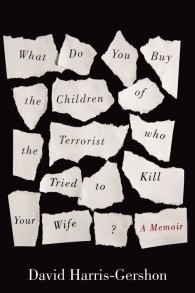

David Harris-Gershon, What do you Buy the Children of the Terrorist who Tried to Kill Your Wife? (London: One World, 2013). 325 pages. $13.70.

David Harris-Gershon has written a brave memoir that charts the traumatic and long-range impact of his wife Jamie’s near-death from a terrorist bombing at Hebrew University in 2002, and his route to healing by trying to understand the motives of the terrorist, Mohammad Odeh.

There are several points of entry into Harris-Gershon’s story: the opening section in which he recounts the bombing and actions of the bomber, his recollections of the aftermath interwoven with the history of his relationship with Jaime, and the summary of the historical context in which the attack took place.

In this way, the reader is introduced to the main players in the precipitating event and its aftermath, as well as to the author’s circumspect style, letting the events speak for themselves, albeit with an occasional literary flourish that lends graphic power to the horrific attack. Here we already see his proclivity to generalize from the personal and particular to the general and universal, as when his convincing description of panic and frustration when first seeing Jaime in the ICU is juxtaposed with his equally convincing description of frustration with Israeli hospital regulations. This juxtaposition of personal memories and reactions, the wall of Israeli bureaucracy, and the historical background of the attack, establishes the stylistic scaffolding of the memoir throughout: the interweaving of past and present, national and personal, time and space.

At times, this intrusion of self can be off-putting, as when Harris-Gershon records his internal dialogues, or passes off a serious concern with what might at first seem too casual, even flippant a tone. In addition to the fact that this is a memoir, however, Harris-Gershon knows exactly how to define and realize the parameters of his story, whether describing the first shock of seeing Jaime’s injuries, his impressive self-insight into his reactions as he witnesses her pain and healing, or the political climate in the summer of 2002 and its roots in the 60s and 70s. Self-honesty reigns as he explores, for example, the romance of transformative tragedy, recognizing after the personal experience of Jaime’s pain and suffering that the urge to join a larger humanity through knowledge and survival of suffering is at best specious, at worst self-indulgent (p. 29); or, when he watches his need to control his environment, his fear of losing control, most poignantly (and humorously) revealed in his fanatical urge to protect his daughter Noa, born after a psychically and physically healed Jaime has outpaced him in the return to pre-bombing normalcy (Ch. 11). Harris-Gershon’s uncompromising self-insight is disarming, and prepares the reader for the crux of the story: because his attempts to heal -- whether through fanatical control of his environment, through psychotherapy, or through returning to study—have failed, he finally realizes that his survivor guilt is misplaced, that he too is a victim of the bombing, and that he is suffering a secondary Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that can be healed in only one way: writing, “not as therapy, but as art….only through storytelling could I reclaim myself.” (133)

And so he begins the quest to understand how and why a terrorist is made. Central to this search is the irony, which he himself points out, of his personal victimhood leading him for the first time to consider the victimhood of the Palestinians, their cultural narrative and history. His journey begins with research into the motives of the perpetrator, Mohammad Odeh and a newspaper report of Odeh’s stated remorse. This is the focus of the memoir. It informs Harris-Gershon’s pursuit of the “truth,” beginning with his curiosity about the South African truth and reconciliation process discussed in Antjie Krog’s Country of my Skull (New York, 1998), and continuing through his outreach to Israeli peace activists, such as Robi Damelin and to an Israeli expert on Israeli Arabs, Dr. Mordechai Kedar. In this section of the memoir, Harris-Gershon shows a journalist’s gift for encapsulating the origins of Zionism and the clash of narratives that condition Jewish and Palestinian claims to the land.

Despite his reliance on single sources for the sections of the book dealing with the Truth and Reconciliation process in post-Apartheid South Africa and the history of Palestinian dispossession by the British, Harris-Gershon’s summaries of both are exceptionally clear, comprehensive, and above all, persuasive. Perhaps that is because he is recounting his own process, his own path to recognizing the humanity of the Palestinians, but it is that path, after all, which forms the substance of this book. Very compelling is the way in which he weaves history, current Israeli- Palestinian affairs and his personal narrative together, as when he discusses the reasons why his attempt to visit the bomber in jail might have been refused by Odeh. His confusion about this, his inability to know for certain who is lying, Odeh or the Israeli prison authorities, in some measure is a metaphor for the instability of both the Israeli and Palestinian cultural inheritance: who is the enemy? Who is the victim? Truth is elusive, whether invoked in the name of reconciliation, or in the name of justification. In Harris-Gershon’s case, his need for psychological healing, his belief in the necessity to meet Odeh in order to shake himself from his trauma, is itself suspect, not least to him.

The crux of the story is here, not in the actual terrorist attack or its aftermath, not in the secondary PTSD he suffered, but in Harris-Gershon’s discovery, ironically as a direct result of the attack, of the need if he were to heal to reconcile with the perpetrator, and the imperative to understand the Palestinian as a human being, his history, his trauma, his narrative, in order to be able to do so.

Back in Jerusalem, as he goes forward with his plan, he is met by the consistent warning that his decision to visit Odeh’s family, even if he is prohibited from meeting with the terrorist himself, literally is crazy and places him in danger, the danger that is inevitable in a volatile world naively believed to be rooted in shared humanity. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the cynicism of the Israelis he speaks to, whether peace activist or taxi driver, rabbi or scholar. Harris-Gershon’s loss of innocence in this regard is convincingly demonstrated by his decision to go forward with meeting Odeh’s family without the thought of revenge, bringing toys for the children, but carrying a knife. At the same time, he is unwilling to share his conviction that what he wanted to do was personal, psychological, and not political, for he knows that in Israel, the political cannot be separated from the personal, and actions always are seen as statements of position. (282) His desire to understand is not the desire to forgive. If in Israel the private may be public, private motivations remain elusive, often to the actor himself, always to the outsider who brings his own agenda to the conversation.

What do you Buy the Children of the Terrorist undoubtedly will dismay and offend those who defend Israeli actions no matter how they violate Palestinian rights. But for those who care or dare to look without prejudice at what the Israeli Occupation has cost both side in the conflict, for those uninterested in the finger-pointing that continues to plague Israeli-Palestinian dialogue, for those who work and hope for a two-state solution, this book is a welcome breath of fresh air, exposing the multiple truths that must underpin reconciliation.

In essence, this memoir wants the reader to make subtle distinctions that more often than not are the first victims of rapprochement. As the concluding moments of this memoir make clear, the truth is not so easy to define. Monstrous acts born of monstrous fears and revenge are perpetrated; monstrously indifferent bureaucracies thrive. And yet, seemingly naïve acts of reconciliation prove to Harris-Gershon, as to all who read this book, that people are not simply monsters. Is it enough?