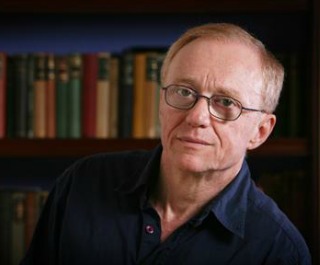

by David Grossman (commentary) in Yedioth Ahronoth

by David Grossman (commentary) in Yedioth Ahronoth

Translation by Israel News Today

The situation in which the Israelis and Palestinians are imprisoned is turning more and more into a sort of hermetically sealed bubble. Within this bubble, over the years elaborate and persuasive justifications have developed for every deed performed by each one of the sides.

Israel can say, justifiably, that no country in the world would keep silent in the face of ceaseless attacks like Hamas’s and threats like the tunnels. Within this bubble, Hamas, as far as they are concerned, will justify their attacks on Israel on the grounds that their people are still subject to occupation, and that the inhabitants of the Gaza Strip are rotting within the blockade that Israel has imposed on them.

Within the bubble of the situation, who can argue with Israeli citizens who expect their government to do everything so that not a single child in Nahal Oz or Sufa or Kerem Shalom will be harmed by a Hamas cell popping up from under the ground in the middle of the kibbutz? And how will we reply to the residents of a bombed-out Gaza who say that the tunnels and the missiles are the only weapon they have left against a power like Israel? Within the hermetic, cruel and anguished bubble, both sides are right, the way they see it. Both of them are obeying the prevailing law of the bubble, the law of violence and war, the law of vengeance and hatred.

But the big question now, while the war is ongoing, is not the question of the horrors taking place every day within the bubble, but the question of how the hell is it possible that we have been suffocating together in this bubble for over a century?

This question, in my eyes, is the most important lesson that we must learn from the latest bloody round. Because I cannot ask Hamas this question, and I do not pretend to understand their way of thinking, I ask the leaders of my country, today’s prime minister and his predecessors: How did you waste all the time that elapsed since the last confrontation without initiating any steps towards dialogue, grappling for a dialogue with Hamas, and attempting to alter the volatile reality between us? Why did Israel refrain in recent years from wholeheartedly entering negotiations with the moderate part of the Palestinian people that is more prepared for dialogue—as well as to create pressure on Hamas? For twelve years, why did you ignore the Arab League’s initiative, which was likely to enlist moderate Arab states who perhaps could have compelled Hamas to compromise? In other words: how is it that for decades, Israeli governments have been incapable of thinking outside the bubble?

Nevertheless, something about the current war between Israel and Gaza is different from those that preceded it. Beyond the invective of a few politicians that has been flourishing in the flames of war, and behind the great show of “unity”—partly authentic and mostly manipulative—something has been happening in this war, something that has succeeded, so it seems to me, in directing the attention of quite a few Israelis towards some “mechanism” at the foundation of the entire “situation”: its sterile, fatal repetitiveness.

Something about the cyclical circular nature of the acts of violence and revenge and counter-vengeance has opened the eyes of many, who until now refused to recognize it, to the picture of ourselves within “the situation.” Suddenly we can see the portrait of Israel with total clarity, a country with amazing powers of creation and invention and daring, which for over a century has been circling around the millstones of conflict, which perhaps could have been resolved years ago.

And if we concede for one moment the rationalizations and justifications with which we protect ourselves from the simple and human sense of compassion towards many Palestinians whose lives have been devoured in this war, perhaps we could see them too, those who are being ground up together with us, in unison, endlessly circling in blind circles and in the numbness of despair.

I do not know what the Palestinians really think in these times and what the people of Gaza think. But I feel that Israel is growing up. With sorrow and pain and gritting its teeth, Israel is growing up, or better—is being forced to grow up. Despite the bombastic proclamations and inflammatory declarations by politicians and commentators filled with hot air, as well as beyond the violent assault by right wing bullies on anyone with a different opinion—beyond all of this, the mainstream of the Israeli public is wising up.

The left wing today is more aware of the power of hatred for Israel—the kind that does not stem from the occupation—and the volcano of Islamic fundamentalism that threatens Israel and the fragility of any agreement signed here. More members of the left wing today realize that the right wing’s fears are not just paranoia, and that they address a substantial and fateful dimension that exists in the reality of our lives. I hope that the right wing today also recognizes—even if it does so enraged and frustrated—the limits of force; and the fact that even a strong country like ours cannot act strictly according to its will, and that in the age in which we live there are no more unequivocal victories, only “pictures of victory” with no real substance. Pictures of victory, whose negatives you can clearly see beyond them, which means that in war there are only losers. This too: that there is no military solution to the true distress of the people facing us. And until Gaza’s sense of suffocation is solved, we in Israel will not breathe easy with our own two lungs.

We Israelis have known this for decades, and for decades we have refused to understand. But maybe this time we understood a little more, or for a moment we saw the reality of our lives from a slightly different angle. It is a painful realization, and certainly menacing as well, but this realization can be the start of a change in perception. It is likely to formulate for the Israelis how essential and urgent it is to make peace with the Palestinians, as a basis for peace with the other Arab states. It can present peace—so ridiculed today—as the best possibility, and the most secure as well, of all the possibilities facing Israel.

Will such a realization also crystalize on the other side, with Hamas? I have no way of knowing that. But a majority of the Palestinian people, represented by Mahmoud Abbas, in fact has already made the decision to forsake the path of terrorism and choose negotiations. Can the Israeli government now, after the blood-riven war we have undergone, after losing so many young loved ones, not at least try this possibility? Will it keep ignoring Mahmoud Abbas as an essential component in resolving the conflict? Will it keep relinquishing the possibility that an agreement with the Palestinians in the West Bank will also lead gradually to improved relations with the 1.8 million inhabitants of Gaza?

And we in Israel, immediately after the war, will have to begin a process of creating a new partnership among ourselves, a partnership that will change the map of narrow sectarian interests that rules us today; a partnership of everyone who realizes the danger of death if we keep circling the millstone. With everyone that realizes that the border lines today no longer separate between Jews and Arabs, but between those who aspire to live in peace and those who are spiritually and ideologically nourished by continuing the violence. I believe that Israel still has a critical mass of people, from the right and the left, secular and religious, Jews and Arabs, who are capable of uniting, soberly and with no illusions, around three or four points of agreement regarding a solution to the conflict with our neighbors; there are many who still “remember the future” (an odd combination of words, and I believe it to be accurate, in this context) —the future they seek and wish for Israel, and for Palestine, too. There are still—and who knows for how much longer—people who realize that if we again sink into apathy, we will leave the arena open for those who will drag all of us, with determination and enthusiasm, into the next war, and along the way they will ignite every possible focal point of conflict in Israeli society.

If we do not do this, all of us, Israelis and Palestinians, collaborators with despair, will keep circling—with our eyes covered, and our heads down from too much dulled senses and idiocy—the millstones of the conflict, which are mashing and eroding our lives and our hopes and our humanity.