In 2003, four former heads of Israel’s secret counter-terrorism service, Shin-Bet, were interviewed by the Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth. Their criticism of then Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s inaction to advance a diplomatic resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict caused an uproar and deeply influenced Sharon. The interview later triggered the award-winning documentary film The Gatekeepers, featuring six past Shin-Bet directors who criticized the political status-quo.

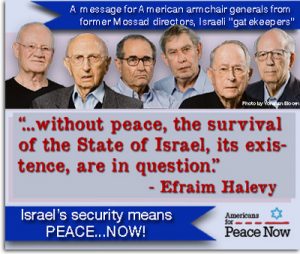

Now, Yedioth Ahronoth is publishing a similar interview with all surviving six past directors of Israel’s spying agency, Mossad: Zvi Zamir (93), Nahum Admoni (88), Shabtai Shavit (78), Danny Yatom (73), Efraim Halevy (83) and Tamir Pardo (65).

Following are excerpts from the March 30th interview with the six (and go HERE to see the series of graphics like the one above):

Yatom: “We’re on a very steep slope. There are serious things that are wrong here. People around the prime minister and people in key positions are being questioned about public corruption, and all of that is because they’ve put their own interests before the state’s interests. I’m worried by the attacks on the gatekeepers and the inaction in the diplomatic realm [i.e. the peace process with the Palestinians], which is leading us to a bi-national state, which is the end of the Jewish and democratic state.

“As a Mossad director, I think it is a mistake for us only to address the period in which we served. In the context of the job we saw a whole lot of things: we saw prime ministers, we saw the decision-making processes in governments. We saw wars. We saw times of peace. And more than many others, we worked closely with the prime minister and with the top state officials. If we don’t say what we have to say, I think that we will be sinning against ourselves.”

Pardo: “The fact that between the sea and the Jordan there is a nearly identical number of Jews and non-Jews. The central problem from 1967 until today is that Israel, across the entire breadth of its political establishment, hasn’t decided what country it wants to be. We are the only country in the world that hasn’t defined for itself what its borders are. All of the governments have fled from coping with the issue.”

Yatom: “The Rabin government didn’t flee from that. He was assassinated.”

Halevy: “Danny is right. 1993 was the only year in the history of the country in which three tracks of peace negotiations were held simultaneously—with the Palestinians, with the Syrians and with the Jordanians.”

Pardo: “But no prime minister ever declared which borders he hoped to have for the state.”

Yatom: “Barak did define. He was willing to leave the Golan Heights and more or less [to withdraw] to the 1967 lines.”

Pardo: Excuse me. I insist on my opinion. The governments of Israel didn’t do that. Olmert had a vision and so did Sharon and so did Rabin. Each one went the single mile that he chose to walk—but none of them said: these are the country’s borders. If the State of Israel doesn’t decide what it wants, in the end there will be a single state between the sea and the Jordan. That is the end of the Zionist vision.”

Yatom: “That’s a country that will deteriorate into either an apartheid state or a non-Jewish state, if we continue to rule the territories. I see that as an existential danger. A state of that kind isn’t the state that I fought for. There are some people who will say that we’ve done everything and that there isn’t a partner, but that isn’t true. There is a partner. Like it or not, the Palestinians and the people who represent them are the partner we need to engage with.”

Halevy: “We’re the dominant [party] and in order to reach any sort of arrangement we have to first of all treat the other side with some degree of equality. Beyond that, we needn’t balk at speaking with Hamas. Hamas was established here 31 years ago. We used everything we have against it, and they still exist. So we can’t ignore that and make do with saying, ‘they’re terrorists.’ Hamas also made a certain change to its charter, which recognizes the 1967 lines as the temporary borders of the state. That’s a big change.”

Question: How critical is the issue of peace to Israel’s existence?

Zamir: “It’s critical. Ultimately, we’re going to have to find a formula that can serve as a basis for a discussion with the Palestinians.”

Pardo: “The State of Israel needs peace in order to exist over time.”

Halevy: “I’ll put it in even starker terms: without peace, the survival of the State of Israel, its existence, are in question.”

Yatom: “My assessment is that if Rabin hadn’t been assassinated we would long ago have had peace with the Palestinians, and perhaps also with the Syrians. As the strongest country in the Middle East we need to take calculated risks and to get back onto the track of dialogue.”

Shavit: “A peace that is based on the idea of two states is a more important interest of the Jews than of the Palestinians. The situation we’re in now is the result of our insistence not to achieve peace.”

Question: Our insistence?

“It’s a lie that there isn’t a partner. Neither we nor the Palestinians are going to make peace voluntarily, of our own will. In this situation, someone is going to come from above who is big and strong and influential and, if need be, will impose that.”

Question: So you’re saying that Israel needs to opt for an arrangement even if it contains elements that are dictated from above, by the Americans or the Saudi?

“Yes. Because when it comes to the question of what we get in return, if we opt for the two-state solution on the basis of the Arab League’s proposal, which was originally written by the Saudis, the biggest dividend that we’re going to receive is a declaration of the end of the conflict with all 22 Arab League states and the establishment of diplomatic relations with them and with another 30 Muslim countries around the world. If tomorrow 50 Muslim countries in the world make peace with Israel and have diplomatic and economic relations with it, we’ll get to see all of the countries that are on our scale—let’s say, all the Scandinavian countries and Holland and Switzerland—see our back [i.e. rank behind us]. Instead of that, what are we preoccupied with nowadays? When is the next time that we’re going into Gaza, and when is the next time we’re going into Lebanon? We need to break that cycle already. Why are we living here? To have our grandchildren continue to fight wars? What is this insanity in which territory, land, is more important that human life?”

Pardo: “I think that within the borders of the country there can’t be first and second-class citizens. Anyone who thinks that over time it’s going to be possible to maintain two classes of population, those with rights and those without rights, is creating a problem for our grandchildren that they won’t be able to cope with, and it could very well be that they will simply leave.”