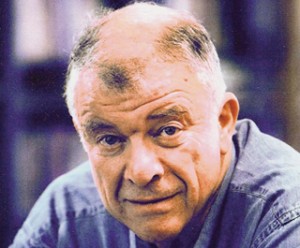

Inspired by stories his father told him as a child, Leonard Fein felt called to mend a torn world, in words and deeds.

Cofounding the magazine Moment with Elie Wiesel in the 1970s, he became one of the nation’s most visible writers and thinkers about Jewish ideas and issues. In 1985 he launched Mazon, a nonprofit that has raised tens of millions to help feed the hungry. A dozen years later he helped create the National Jewish Coalition for Literacy to train tutors, and he also was a founder of Americans for Peace Now.

Yet to those he met day to day, his private presence was as profound as the public actions and writings that touched uncounted lives across the country. Scholars and leaders praised Dr. Fein when he died, and so, too, did his cleaning lady, who told his daughters she felt she “was in a room with greatness” when she tidied his home and he paused to chat.

“Yes, he was an extraordinary person in the world, but he also was an extraordinary person

one-on-one,” said his daughter Jessica of Framingham. “What he meant to me and my family on a daily basis was in

my opinion much more extraordinary than what he contributed to the community and the world. He was my best

friend. He was somebody with whom I spoke several times a day. He was just incredibly present.”

“Yes, he was an extraordinary person in the world, but he also was an extraordinary person

one-on-one,” said his daughter Jessica of Framingham. “What he meant to me and my family on a daily basis was in

my opinion much more extraordinary than what he contributed to the community and the world. He was my best

friend. He was somebody with whom I spoke several times a day. He was just incredibly present.”

Dr. Fein, who lived in Watertown, collapsed in an elevator on the way back to a residence he kept in Manhattan and died Aug. 14. When he turned 80 several weeks earlier, family and friends held a celebration at The Cloisters in New York City. Dr. Fein, who was known for his ready humor, as well as his intellectual prowess, listened to tribute after tribute and then quipped to Jessica, “I’ve just heard all my eulogies.”

Known as Leibel, Dr. Fein was a columnist for The Jewish Daily Forward, and his most influential books included “Israel: Politics and People” and “Where Are We? The Inner Life of America’s Jews.”

“Throughout his life, Leibel took his personal experiences, grief among them, and found inspiration to strengthen others,” Rabbi David Saperstein, who directs the Religious Action Center in Washington, wrote in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz.

Never was that more the case than when Dr. Fein wrote a book about the 1996 death from heart failure of his daughter Nomi, who was 30. “I understood from the start that the act of writing was a way both to keep her alive and to accept the fact of her death. And I needed to do both,” he wrote in “Against the Dying of the Light: A Parent’s Story of Love, Loss and Hope,” published in 2001.

Dr. Fein “had the rare ability to put his thoughts on paper in a way that persuaded, enlightened, and altered your thinking, while all the while your mind was carried along by the beauty of his eloquence,” Debra DeLee, president of Americans for Peace Now, wrote after he died. “He used words as an artist uses paint – it was beautiful and powerful, while the content was often courageous and bold.”

Born in New York City, Leonard Fein moved with his family to several cities across the continent as his father, Isaac, a college professor of Jewish history, and his mother, Chaya, who taught at the elementary level, sought work. Finishing high school in Baltimore, he went to the University of Chicago, which he considered “the only serious educational institution in the country,” Jessica said. After graduating, he received a doctorate from Michigan State University.

While in Chicago he met Zelda Kleiman. They were married 19 years and had three daughters. Their marriage ended in divorce, as did a second marriage, to Sharon Cohen.

Dr. Fein taught political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Jewish studies at Brandeis University before starting Moment with Wiesel and working as a writer the rest of his life.

In his book “Where Are We?” he wrote that he wanted to examine large and small questions that “touch on the lives of American Jews. It is about how we have sought to answer such questions, explicitly or implicitly, ingeniously, or clumsily. It is about our commitments and evasions. . . . It is about the pride so many of us feel in being Jewish, and the paralysis we suffer when we try to explain what being Jewish, here in America, and now, means.”

In his parallel career as an activist, “Leibel was first and foremost a visionary – someone who saw what was broken in our world and saw with equal clarity how to repair it,” Abby J. Leibman, president of Mazon, wrote in a tribute published in The Jewish Journal.

Dr. Fein conceived the idea for Mazon while visiting a friend in California. Watching a caterer pull into a synagogue parking lot in a BMW got him thinking about how some $500 million was spent annually across the country on celebrations such as bar and bat mitzvahs.

“It occurred to me that if we could encourage people voluntarily to add a 3 percent surcharge to the cost of those celebrations, we could generate a very significant fund for the battle against hunger,” he told the Globe in 1986, a year after founding Mazon.

It was, he said, “the only ‘eureka’ idea I ever had in my life.” Soon after inspiration hit, he explained the idea to his daughter Rachel Davidson of Bedford, N.H., while they shared a meal, and “it was so brilliant I had to put down my fork,” she recalled. “But does anybody have an idea and make it happen?” Her father could, and did.

“He had this ability to live his moral view and bring it into everything he did,” she said. “Even as we were growing up, he was someone who was going to change the world. He talked about it eloquently and wrote about it eloquently and made it happen.”

A service has been held for Dr. Fein, who in addition to his two daughters leaves five grandchildren.

His older brother, Rashi , who died a week ago, delivered a eulogy at his brother’s service, and said “the way to honor Leibel is by telling of his accomplishments so that they inspire us and remind us that there are people who don’t look like a little engine, but who say ‘I know I can, I know I can,’ and then do.”

Still, that’s not enough, said Rashi, who was a professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School. Those present, he added, could best “honor Leibel by trying to be a Leibel.”

When Dr. Fein was in his 50s, he composed a letter to his daughters to be opened after his death. “I long ago said to you that you were born into a life of privilege,” he wrote, adding that they were “compassionate children of compassionate parents . . . seek to be links in that chain, to become, in your turn, the compassionate parents of compassionate children.”

Invoking the Hebrew phrase tikkun olam, to repair the world, he encouraged them to “make a difference . . . in whatever ways are given you, in whatever ways you can.”

At the conclusion, he mused that he would have “liked to know how the story ends, but the fact is that the story never ends. All that changes is who gets to write it. I hand my pen to you; write well.”

This article first appeared September 15, 2014, in The Boston Globe