This is another in a series of reviews of new books on Middle Eastern affairs. We asked Dr. Gail

Weigl, an APN volunteer and a professor of art history, to review Sandy Tolan's new book about young

Palestinian using the power of music to transform their lives under occupation.

This is another in a series of reviews of new books on Middle Eastern affairs. We asked Dr. Gail

Weigl, an APN volunteer and a professor of art history, to review Sandy Tolan's new book about young

Palestinian using the power of music to transform their lives under occupation.

APN's Ori Nir interviews Sandy Tolan.

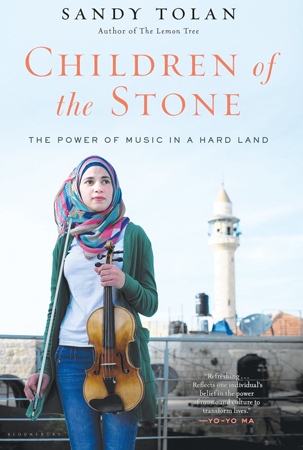

Sandy Tolan, Children of the Stone: The Power of Music in a Hard Land (New York, 2015). 438 pages. $28.00.

Sandy Tolan’s Children of the Stone: The Power of Music in a Hard Land reads like fiction, but is a meticulously documented work of non-fiction, as the author makes clear in his introduction to the extensive source notes. While the book remains focused throughout on the main protagonist, Ramzi Aburedwan, his musical training and successful effort to bring the healing power of music to the Palestinian communities of the Israeli Occupied Territories, equal – if not more attention – is devoted to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, from the founding of Israel to the present. The stage for Ramzi’s story is never-ending physical and emotional violence perpetrated against the Palestinian people by the Israeli government and IDF. That history is interconnected with the more or less extensive stories of many Palestinians, Europeans and Americans devoted to music as the means to assuage Palestinian suffering and restore Palestinian honor and identity.

Because Children of the Stone is written from a Palestinian perspective, and although Tolan documents every reported Israeli abuse—often citing government officials, journalists and Israeli human rights activists—there is little to no sympathy for Israeli responses to Palestinian actions and reactions. Even when reporting the most egregious acts of terrorism against Israel, Tolan’s interest lies in dispelling myths that support an Israeli narrative of victimhood, finding the precipitating factors to be Israeli violations of Palestinian autonomy, honor and dream of a contiguous state with East Jerusalem as its capital. Hence, even the most liberal critic of Israeli policies in the West Bank and Gaza will find Children of the Stone a difficult read: the facts that emerge from the narrative and accompanying notes are often shocking—the torture of a Palestinian musician, the deliberate provoking of riots, the bulldozing of homes, the arbitrary delays and denials of travel—and certainly are horrifying.

In this sense, Children of the Stone is two, possibly three books: it is the story of Palestinian longing for a land lost to the state of Israel, and the memories that inform that longing; the story of Palestinian acts, ranging from diplomatic negotiations to violence against Israel and the Israelis; the story of Israel’s diplomatic and military responses to those acts; the story of Ramzi’s musical baptism and education, and his unparalleled, truly remarkable establishment of the Al Kamandjati (“The Violinist”) music schools in the Occupied Territories; the story of the efforts and commitments, dreams and disillusion of those who guided, supported and opposed him; the story of Ramzi’s growing conviction that music is not merely a pleasure and a balm, but a potent force to bridge enmity, and bring to Palestinian communities an experience of joy and accomplishment that transcends the daily humiliation and bitterness of settler violence, separation barriers, checkpoints, imprisonment and death; the story of conflicts within conflict, as Ramzi increasingly becomes politicized away from the humanistic message of music, breaking with every mentor who remained committed to the communicative and unifying power of music; it is, finally, the story of Ramzi’s refusal to participate in music making that ignores realities on the ground, thereby normalizing Palestinian suffering and deprivation.

The precipitating event in Ramzi’s life and of Tolan’s book was a photograph of 8-year-old Ramzi

hurling a stone during the first Intifada, angry at Israeli soldiers who had interrupted his game. So

powerful was the image, Ramzi became the poster boy for the rebellion embodied in

the Shabab, the “Children of the Stone.” The image captured the ferocity of his anger,

ultimately channeled into music, but always fueled by the need to provoke, and to return to the village and way

of life preserved in his beloved grandfather (Sido) Mahammad’s memories, inculcating in Ramzi a deeply felt

nationalism and idealization of Palestinian losses. In Tolan’s telling, every destroyed or confiscated

Palestinian village once had been a bucolic center of olive groves, orchards, wheat fields, grazing livestock

and whitewashed houses.

The precipitating event in Ramzi’s life and of Tolan’s book was a photograph of 8-year-old Ramzi

hurling a stone during the first Intifada, angry at Israeli soldiers who had interrupted his game. So

powerful was the image, Ramzi became the poster boy for the rebellion embodied in

the Shabab, the “Children of the Stone.” The image captured the ferocity of his anger,

ultimately channeled into music, but always fueled by the need to provoke, and to return to the village and way

of life preserved in his beloved grandfather (Sido) Mahammad’s memories, inculcating in Ramzi a deeply felt

nationalism and idealization of Palestinian losses. In Tolan’s telling, every destroyed or confiscated

Palestinian village once had been a bucolic center of olive groves, orchards, wheat fields, grazing livestock

and whitewashed houses.

The opening chapters establish the format throughout. Tolan writes cleanly, with journalistic detachment and a gift for creating word pictures, describing what the reader would take as the parameters of normal life, and then shattering the appearance of normality with eruptions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It is a very demanding format, perhaps somewhat disingenuous, as the reader absorbs Ramzi’s remarkable story unaware at first of the importance of the end notes, listed at the back by pages referencing lines of text. This necessitates flipping back and forth from text to notes, interrupting the flow of the narrative to check the documentation, and creating some difficulty following the mood or circumstances of the narrative itself. However irritating this may be, the notes are critical to the interweaving of Ramzi’s biography with the harsh realities of Israeli occupation. Not only do they validate and substantiate the facts, emotions and attitudes reported in the narrative, they also expand the historical record. If Children of the Stone is the story of great ambition, courage, persistence and triumph under military occupation, the notes inform us of dehumanizing acts that are the inevitable by-product of occupation, whether perpetrated by the Israelis, or by the Palestinians against themselves and their own interests.

The focus on Ramzi effectively personalizes and humanizes the context that influenced his struggle to pivot from an angry child to a passionate musician and founder of Al Kamandjian. The process begins with two inspirational figures, music therapist and violinist Mohammad Fadel and the Christian clarinetist Surhail Khoury (imprisoned and tortured by Israel), who believed they could be part of the “cultural renaissance of an independent Palestinian state” (58) by building a classical music conservatory in Ramallah. At their small National Conservatory of Music (Ma’ had) Ramzi began to learn viola under Fadel, and within a year had mastered the instrument sufficiently to attract the attention of a group of chamber musicians in Ramallah on a cultural mission for the Consulate General of the United States in East Jerusalem. They represented the program that would provide Ramzi’s first experience outside the emotional and physical demands of daily life in Ramallah. At 18, he became a student at the Apple Hill Center for Chamber Music in New Hampshire. There, among fellow students from Europe and the Middle East, including Israel, Ramzi experienced his first serious training in music practice and theory, and was introduced to canonical works of European classical music. Tolan is particularly effective here as he captures the magnitude of Ramzi’s introduction to worlds undreamed of, and his trajectory as a musician, from that life-changing, life-enhancing beginning through scholarship study in France at the Conservatoire d’Angers for two years, and his return to Ramallah to teach and perform at the Ma’had.

After his experiences abroad, the oppressive circumstances of the Occupation and the failure of the Oslo accords to provide a roadmap for peace and the establishment of a Palestinian state became yet more difficult to endure. This would lead Ramzi finally to abandon the notion of bringing enemies together through the alchemy of music. As Tolan charts Ramzi’s development in Angers as a musician and political activist, conflict emerges as a leitmotif of his life. His elementary musicianship compared to that of his Israeli counterparts, and his growing awareness that his Palestinian identity was a major reason for his invitation to join the youth orchestra were endless sources of irritation, even anger. During these years, the tension between his identity as a student of European nusic and his Palestinian identity increasingly was resolved by playing Arabic music in an Arabic-French band Dalouna, founded with fellow students. As Dalouna absorbed his energy and attention, Ramzi’s classical studies suffered, but the anger that informed his playing infused it with a passion and intensity that transcended technical weaknesses.

Ultimately, the vision of two remarkable men would prove the most important influence shaping the adult Ramzi. The great Palestinian-born philosopher Edward Said and the Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim formed an unlikely friendship from a chance meeting, and together envisioned a parallel alternative to the collapsing Oslo peace process: the creation of a Palestinian state as a haven of high culture. Said’s denunciation of Oslo and his desire to bring people together found a kindred spirit in Barenboim. Together they sought to create a musical enterprise that would provide an antidote to violence, cynicism and mistrust. With support from the renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma, they created Divan, a youth orchestra dedicated to playing classical music, principally of the German tradition, and rooted in the proposition that European, Israeli and Arab musicians could cooperate to produce a singularly powerful musical voice, thereby transcending their political and cultural differences. Much of Children of the Stone focuses on the development and philosophy of Divan, including Said’s insistence that Germans and Arabs recognize and understand the trauma of the Holocaust, without absolving Israelis of their responsibility to acknowledge the suffering of the Palestinians exiled from their homes and barred from creating their own nation-state. A sub-text here is Said’s death from leukemia, and Barenboim and Said’s wife Miriam’s continued commitment to Divan.

The unrelenting Palestinian-Israeli conflict and Israeli occupation continued to politicize Ramzi to the point that he broke with Divan and hence, with Barenboim and Miriam Said. That story concerns Ramzi’s growing belief that Divan had to take an uncompromising stand condemning the Israeli Occupation and expressing solidarity with the Palestinian people. Increasingly, he came to identify with non-violent resistance, believing that Divan’s message of “harmony between traditional enemies obscured the truth on the ground.” (270) Ramzi’s break with Divan is pivotal and deeply symbolic of the tragedy of Israeli-Palestinian enmity. Much of the narrative in the later sections of Children of the Stone concerns the conflation of music and politics, Ramzi’s refusal to uncouple the two, and his subsequent identification with the BDS movement—to the degree that he came to view members of Divan as collaborators with Israel.

Suffice to say, Tolan’s text is uncommonly dense and demanding, touching as it does on the existence of Israel, the Nakba, the Occupation, Palestinian resistance and dream of statehood, and the boycott movement, all wrapped up with the personal, professional and political meaning of music. The scope of Ramzi’s story, embedded as it is in Tolan’s sympathy for Palestinian suffering, leads to a profound respect for Ramzi’s achievement despite a lifetime of poverty and violence, and admiration for those who helped bring music education to the children of the Occupied Territories, from Said and Barenboim, to the musicians, music teachers and therapists who came from Europe, the United States, Israel and Arab countries to work alongside Ramzi. From teaching, to administering, to hosting, they helped in innumerable ways to create Al Kamandjati, and Tolan acknowledges their contributions throughout.

Tolan writes with great conviction and descriptive power. The range and depth of his knowledge is impressive. But the numerous storylines are complicated, and as he transitions from music to personal biography, from the detailing of Israel’s policies to the minutiae recorded in the textual notes, the reader becomes entangled in an excessively episodic narrative. The problem is exacerbated by the cross-cutting cinematic organization of the book, as the narrative rapidly veers from one scene to another, from, for example, Ramzi’s music education to the failure of the Oslo Accords to Israeli settlement activity. The story Tolan tells is comprehensive and critical to understanding the Israeli-Palestinian quagmire. The trajectory of Ramzi’s transformation from stone-throwing boy to mature musician and founder of music academies is deeply moving and inspiring, as is the work of many others who formed and aided Ramzi’s vision, and the power of music to heal and uplift. Nevertheless, Children of the Stone might have benefited from a sympathetic editor.