Yossi Alpher is an independent security analyst. He is the former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University, a former senior official with the Mossad, and a former IDF intelligence officer. Views and positions expressed here are those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent APN's views and policy positions.

Q. The hot topics this year are the rise of the ultra-nationalist right, Putin, the Mossad, Hamas and, for the diehards among us, mediating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Can you start with the looming ultra-nationalist right?

A. Read Madeline Albright’s Fascism: A Warning (HarperCollins, 2018). It’s an

easy read. Its author’s life spans from Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin all the way to Trump. Yes, she rambles

autobiographically on topics not always entirely relevant. But she has had an interesting career--in academia, at

the United Nations and at the State Department--that more than qualifies her to speak out about where the world is

going.

Albright knows her fascism and she knows how to integrate the history of fascism as an ugly political philosophy

into what is happening today, from Hungary to Venezuela, from Erdogan to Putin. Her chapter on the Koreas is

particularly timely. Her biggest lacuna is not even mentioning what is happening in Israel (last year I noted Colin

Shindler’s The Rise of the Israeli Right from Odessa to Hebron).Yet her book is required reading for

anyone trying to understand the broader global backdrop to what is happening in Israel.

So is Michiko Kakutani’s The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump (Tim Duggan Books,

2018). It provides an intelligent and thoughtful backdrop to the handmaidens of fascism, fake news and the decline

of reason.

Q. Albright discusses Putin. Last year you mentioned Putin’s Russia. Any other good reads about the Russian president and the Russia he presides over?

A. Masha Gessen has recently published two useful books. The Future as History: How

Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (Riverhead, 2017) puts the events of recent decades into perspective by

following the vicissitudes of a number of interlocking figures. The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of

Vladimir Putin (Penguin, 2012) was written before the Russian president brought his country and his armed

forces back to the Middle East and before he annexed Crimea and undermined Ukraine. In any case it focuses

primarily on internal Russian factors. The description of Putin’s boyhood and youth is particularly interesting for

anyone trying to understand him.

Putin, his legions and his machinations in Syria are currently Israel’s major strategic preoccupation. Gessen’s

books are helpful in understanding Israel’s new neighbor.

Q. The Mossad, Israel’s clandestine intelligence service, seems to have become an “in” topic. Last year you mentioned your own narrative of a Mossad-run grand strategy, Periphery: Israel’s Search for Middle East Allies. What do you recommend now?

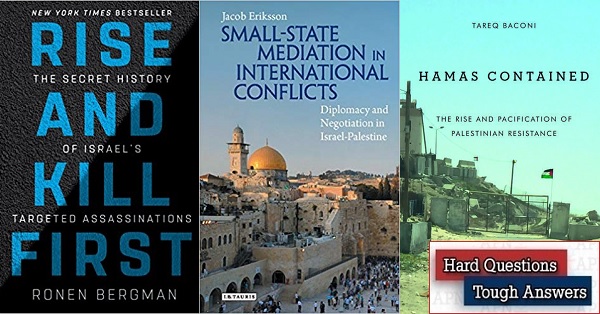

A. Ronen Bergman’s book, Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel's

Targeted Assassinations (penguinrandomhouse, 2018) leaves the unfortunate impression on the reader who plows

through its 750 pages that all Israel’s intelligence arms really do is kill people. This is factually and ethically

wrong. Nowhere does the author seriously explain that he is focusing only on a single aspect of Israeli

intelligence and special operations over the years, and that most Israeli intelligence professionals are neither

trigger-men (and women) nor bomb-makers.

Still, Bergman is a serious writer and a deep thinker. He has written an extremely well-researched and

comprehensive book explaining why and how the pre-state Yishuv, followed by the State of Israel, have resorted to

physically targeting some of their enemies.

A Mossad Agent in Southern Sudan 1969-1971: An Operational Log, by David Ben-Uziel (Tarzan) (Teva

HaDvarim, no date, 2016 or 2017) tells the truly amazing story of Israel’s military support for African rebels in

South Sudan fighting against the brutal oppression of the Arab regime in Khartoum. The story is a must read for

anyone wishing to understand how the southerners eventually won their independence a decade or so ago, how the

dynamic of Arab-black African relations has transpired over the past century, and the absolute significance of the

Nile River for Sudan and Egypt.

At a broader level, Ben-Uziel’s book explains how and why the Mossad came to “adopt” this particular African

freedom struggle against the broader backdrop of Israel’s efforts to leverage the Middle East periphery against the

Arab core--at the time its existential enemy. True, the southerners have in recent years squandered their

independence and descended into horrific civil war. That issue, not dealt with in this book, troubles any and all,

this writer included, who helped the southern Sudanese fight Arab imperialism and racism.

Ben-Uziel (Tarzan became his permanent nickname in the 1950s, thanks to a fortunate rescue of a drowning boy at a

time when Johnny Weissmuller movies were playing in Tel Aviv’s cinemas) was the dominant Israeli figure in this

operation. Decades later, he was permitted to describe it--in the first person, not at all shy about his role, and

with his own excellent photographs.

Q. And films?

A. As a Mossad veteran, I’m pretty picky about fiction films that depict the Mossad.

Shelter, a 2017 Israeli production directed by Eran Riklis and featuring some fine acting by Neta Riskin

and Golshifteh Farahani, is based on a Hebrew short story several decades old. Its late writer, Shulamit Hareven,

set the story in Paris; Riklis, to keep it trendy, has moved it to Berlin.

The plot is probably convincing to most viewers. Inevitably, I found lots of operational and character

inconsistencies. That is almost always what happens when you turn real elements of espionage into a story or a

film. See for example John le Carre’s excellent books and their film versions: all the key characters seem to me

positively creepy by real-life intelligence standards.

The Mossad: Imperfect Spies (2017, Zygote Films) is an Israeli-made documentary comprising extensive

interviews with Mossad veterans, arranged loosely by topic. The original Hebrew version, about four hours long, was

shown as a series on prime-time Israeli TV this year. The operations discussed in the series go back

decades--otherwise none of the interviewees would have been permitted to talk.

This is the most accurate and comprehensive film about the Mossad that I know of. English, French and German

(subtitled or dubbed) versions are becoming available. It is scheduled for Netflix in 2019.

(Full disclosure regarding Mossad books and films: I am mentioned in the Bergman and Ben Uziel books. I knew the

late author of Shelter, Shulamit Hareven, whose late husband was my first boss in the Mossad. She wrote

this story originally under a pseudonym, which is presumably the only way she could publish it without compromising

her spouse. And I am interviewed at some length in The Mossad: Imperfect Spies.)

Q. Hamas?

A. Certainly a hot topic. Tareq Baconi, a Palestinian based in London, has just

published Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (Stanford University Press,

2018).

This is a well written yet problematic book. Obviously, in weighing my response to it the reader of this brief

review should bear in mind that these are the insights of an Israeli Jew reading an attempt by a highly intelligent

Palestinian to write as objectively as possible about militant Palestinian Islamists.

Baconi offers us a long and repetitive blow-by-blow account of Hamas’s fortunes since the movement emerged in Gaza

in the late 1980s. His narrative is comprehensive and undoubtedly useful for researchers. But, aside from a few

perceptive pages in the conclusion, it lacks an analytical dimension.

I looked in vain for any serious discussion of Hamas’s approach to: a) two failed peace processes--Olmert/Abbas

2008 and Kerry 2013-14; b) suicide bombings as a cultural-religious phenomenon; c) the meaning for future

Israeli-Hamas relations of recognition by Israel, as demanded by Hamas, of the right of return as part of a

hudna or long-term ceasefire; d) similarly, the significance of Hamas’s call for Israel’s ultimate

disappearance as a factor in Hamas-Israel relations. Repeated abortive Palestinian unity government (PLO-Hamas)

attempts are placed chronologically in the narrative with little attempt to assess the strategic ramifications of

this important phenomenon.

And there are factual errors, e.g., “On June 5, 1967, President Nasser in Egypt mobilized his ground forces in the

demilitarized Sinai Peninsula. . . “ (that happened in mid-May 1967). Hamas figures for Gazan losses in wars with

Israel are cited unquestioningly without even mentioning Israel’s alternative figures. The writer ignores the

aspect of the 2005 Gaza withdrawal that reflected PM Ariel Sharon’s basically hawkish need to get President Bush 43

off his back and push US peace process urgings to the back burner. In general, the writer appears to know far too

little about Israel.

So why recommend Hamas Contained? I thought I knew a lot about Hamas, yet found the book a worthwhile,

well researched and well written refresher. For a reading public that might know even less about Hamas yet wants to

try to understand what makes the Gazan leadership tick, this is a good place to start, however cautiously.

And for those who still believe that well-intentioned and concerned outsiders can make a difference in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

A. Jacob Eriksson, a British academic with Swedish roots, has written about Swedish and

Norwegian mediation attempts in Small-State Mediation in International Conflicts: Diplomacy and Negotiation in

Israel-Palestine (I.B.Tauris, 2015). Lest we forget, in their day both Oslo (the 1993 Oslo Accords) and

Stockholm (the 1995 Beilin-Abu Mazen Understandings) registered significant achievements in advancing the cause of

a two-state solution through sponsorship of secret back-channel talks.

Eriksson shows how small states that boast accomplished diplomats and are perceived by conflicted parties as

objective, discreet and lacking in ulterior motives, can do this sort of thing better than major powers.

Ultimately, though, “when the time comes to close on a final agreement, a manipulative mediator who uses their

political and economic leverage effectively will be required.” That still means the United States.

In the Trump era, don’t hold your breath.